Large-format photography in the 1980s

Condensed version of a lecture by H. C. Koch, Dipl. Ing. ETH, given at a meeting of the Institute of Incorporated Photographers in London, at an Industrial Photographer’s convention in Stockholm and to the “Sinar-Fan-Club” in Osaka and Tokyo, Japan.

Professional photography in the 1980s will stand in the light of technical progress in hardware, and in the shadow of raw material shortages, including silver and hence all film materials. Looking at specific areas in these terms gives us an idea of the trends facing professional photography in the 1980s, especially concerning large-format use.

The question of format

Amazingly, so far only a minority of the world’s population takes photographs. Yet picture taking is becoming simpler all the time and equipment easier than ever to use. So amateur snapshot photography is likely to increase on a broad front.

Against this, the professional photographer can survive only by making his product stand out from that immense mass of more or less random picture generation. Apart from high-quality aclion photography, the real strength of the professional lies in large-format view camera techniques where he can compose single shots with complete control of quality and image effects. Obviously the allrounder must continue to work with all picture sizes from 35 mm up; the professional will however face a distinct shift of demand towards best possible single pictures.

Taking materials

As far as taking materials are concerned, the question is wide open whether and how far electronic image recording with CCD systems can replace chemical sensitized films. Despite considerable work and rapid progress in the field of electronic image recording, we at SINAR do not think that this development is likely to spread appreciably during the 1980s.

Photochemical film is likely to maintain its position, for its resolving power is unparalleled and system cost still far below that of electronic alternatives. Where the photographer must immediately deliver his shots, instant-picture systems provide the answer. These are likely to be perfected further during the 1980s and should also encourage the trend towards large-format work by providing unenlarged instant prints as originals.

Lenses for large-format

view cameras

The essential developments in view camera lenses took place in the 1950s and 1970s. The latest advances are based on:

- Computerised lens design (more advanced optimised calculation programs) and the use of new glass types;

- Multicoating, leading to reduced flare and increased image contrast.

Apart from slight gains in lens speed, the 1980s are unlikely to bring fundamental changes. However we shall have to establish likely requirements in focusing and exposure technique to benefit in practice from the very high performance of the new lenses. The graph Fig. 1 shows how image performance is related to the aperture used in an exposure, comparing older lenses with newer computerised designs.

As a result of reduced image aberrations, the new lenses evidently yield high performance already at large apertures. At small apertures however both lens types are equally subject to diffraction effects of the small lens opening. And as diffraction is a physical phenomenon, it cannot be improved by modifying the lens design. Multicoating in turn yields images with reduced flare and hence better contrast transfer.

For the ultimate image

Important conclusions:

The improved definition of modern lenses makes it feasible to use them at larger apertures; on the other hand their quality advantages are lost on stopping down. In this, modern lenses differ from older ones whose performance improved the more they were stopped down. So we need a new working approach based on using lenses at the largest possible aperture. That in turn calls for more exact view camera focusing and adjustment. Hence we have to drop trial-and-error procedures of sharpness distribution control (by the Scheimpflug converging planes principle) and we have to give up depth of field control by stopping down the lens (which yields a dark screen image, anyway).

Improved lens performance thus logically demands a camera with appropriate modern adjustment aids. For the image sharpness of the best and most expensive lens still depends on how accurately it ist focused. We assume also that the lens is precisely mounted on the lens board within equally tight tolerances (lenses factory-mounted by SINAR, engraved with ‘SINAR‘ on the lens itself). Reduced flare through multicoating in turn improves contrast rendering. This quality improvement can again be utilised only by a suitable approach to picture taking and reproduction (contrast control).

Technical progress – as in other fields – thus tends to modify the working techniques required. That is another aspect of the 1980s.

Large-format

view camera designs

We can distinguish three different basic designs, with following outlook for the 1980s.

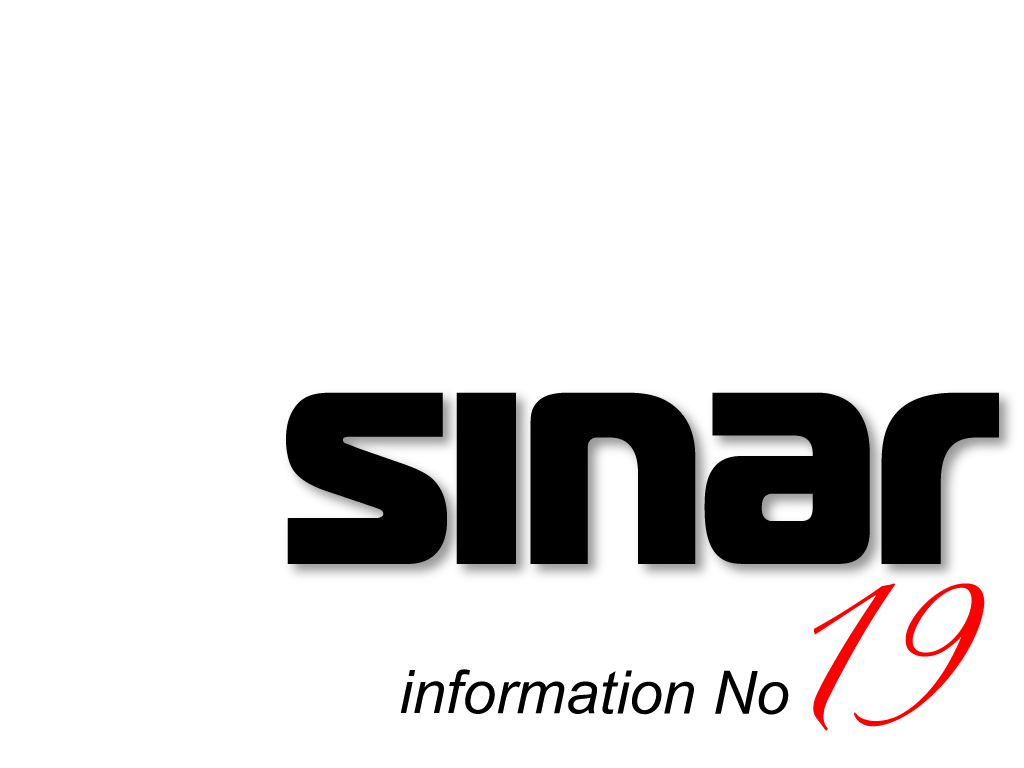

The baseboard-mounted technical camera Fig. 2

This design is compact but limited in adjustability and in usable focal lengths. Users of this camera type have for some time tended either to switch to medium-format or 35 mm cameras or to turn to the monorail camera. This trend is likely to continue.

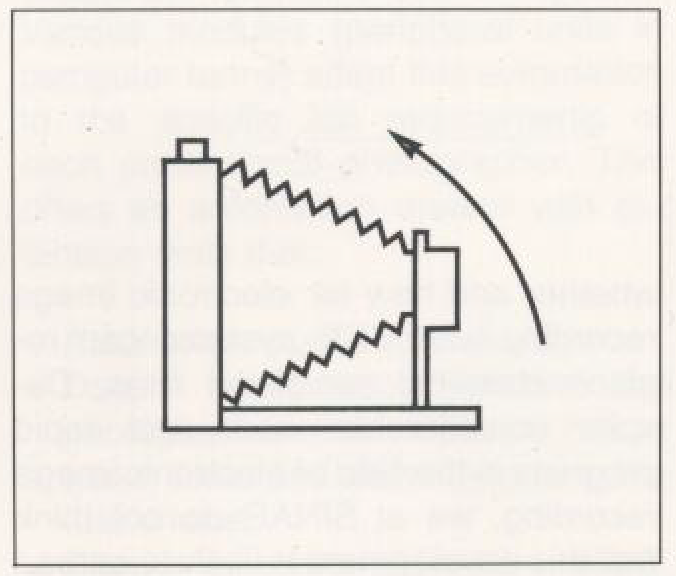

The single-format monorail view camera with fixed components and bellows Fig. 3

The performance limits of this camera are the same as for the baseboardmounted technical camera but without the compactness of the latter. Its low price gives this camera type a certain market following. But it cannot cope with special jobs of any complexity – there it lacks flexibility and scope for extension.

The modular monorail camera Fig. 4

The universal modular system with interchangeable parts meets the professional photographer’s requirements for individual image control beyond the scope of the amateur snapshooting masses and offers the superior quality of the large-format picture.

Since a single camera can hardly ever serve as an ideal universal camera in the studio as well as on location, the system allows the basic camera to be adapted to different needs. Interchangeable components require a much higher manufacturing precision and are therefore correspondingly more expensive. But as each component can be used in different ways, the overall investment in a modular view camera system is less.

The photographer does not have to acquire alternative systems for different formats and jobs in and outside the studio. Quality-conscious professionals will therefore increasingly use this camera type in the 1980s.

For the ultimate image

Focusing and image

control

Even with ideal lens and camera specifications, the final result on the film still depends entirely on point-bypoint focusing on the ground glass screen. We may note that at a normal viewing distance of 30 cm or 12 inches the human eye can resolve detail down to about 0.1 mm. We see a whole picture and its individual image points in a certain subjective way; by selective sharpness control we must be able to convey that subjective impression in an objective image.

The following aids will contribute more and more to meeting this requirement in the 1980s:

- An optimum screen image with ideal viewing aids for an overall view and for assessing each individual image point; also a suitable screen design.

- Precision point-by-point focusing by micrometer adjustments for all camera settings {focus, lateral and vertical shifts as well as swings and tilts) which must be as accurate as focusing. Equally important is a methodical point-by-point adjustment of the plane of sharpness and of the required perspective. Moreover once a point is focused, this must remain fixed while focusing other image points. In other words, we must get away from trial-and-error approximations.

Establishing exposure

data

Increased film prices (the raw material), higher image contrast through multicoating and increased processing costs and services will make it essential to secure better quality more precisely with less film consumption. The technical tools are already available for more precise exposure measurement and adjustment.

Exposure measurement: There will be a further shift towards spot metering in the film plane {where the image is exposed) – and this will also cover flash exposures. By locating measuring points with a movable probe window it is possible to establish the precise lighting, exposure time and brightness range and to make appropriate corrections in the lighting setup. Nor does this mean wasting valuable time and materials. Electronic engineering will here eliminate many complications and sources of error.

Shutter speeds: Universal shutters will increasingly replace individual between-lens shutters in every lens. (After all, this is standard practice in virtually all 35 mm reflex cameras.) Digital engineering makes effective shutter speeds much more precise and also permits professional third-stop intervals with simultaneous compensation of shutter speeds and apertures. The moving sector system (freely rotating blades with SINAR) yields even exposure from the picture centre to the edge, with all lenses and at all stops. An increased shutter speed range also extends the scope for aperture selection and makes for more flexible pictorial control (high shutter speeds even in view cameras to long times beyond 1 second).

Apertures: Uniform iris diaphragm design in all lenses makes for more precise settings.

Error-free rapid operation calls for precise sub-division into professional ½stop steps (like shutter speeds) and automatic stopping down after preselecting the aperture and setting it on the shutter.

For the ultimate image

Automation

This is the computer era; electronics made amateur cameras fully automatic ages ago. The professional large-format camera on the other hand needs appropriately tailored automation because the professional must be able to select any combination ov basic exposure settings.

The precision-engineered view camera with up-to-date lenses, improved focusing and modular construction will therefore find itself complemented by a modular electronic microprocessor system. The basis (central processing unit in computer terms) is the DIGITAL shutter with its microprocessor system. Various modules (peripheral units in computer terms) adapt this automation to the specific job requirements of each professional photographer. This offers an automation system with extension units that:

- Automates routine operations;

- Despite automation shows the photographer what choice he has to make when and allows him to make that choice;

- Shows selected alternative exposure combinations;

- With the built-in exposure computer permits adjustments right up to the last instant before taking the picture itself.

The electronic modular system fits into the existing mechanical modular system and allows every user to modernise his working procedures step by step – without replacing old camera models by new ones.

The new units will further simplify the work of the view camera photographer. They will help him to realise creative ideas, but reduce operating time and material consumption by simplified application.

The essential requirement remains QP: timum image quality of every view camera picture. These hardware developments described will help the professional photographer of the 1980s to keep his standards above the growing mass of pictures.

SINAR LTD SCHAFFHAUSEN

CH-8245 Feuerthalen, Switzerland

Telephone: (053) 5 45 27

Telex: ch 76740

Cables: SINAR CH 8245 Feuerthalen